2. THE INTEGRITY OF THE MACHINE

On november 30th, 1661, Huygens wrote to his brother:

“Ma pompe pneumatique a commencè d'aller depuis hier, et toute cette nuict une vessie y est demeurée enflee, (sans que pourtant il y eust auparavant presque aucun air dedans) ce que jamais Monsieur Boile n'a pu effecteur. [My pneumatic pomp has started to work since yesterday, and the whole night a bladder stayed inflated in it (even though before, there was almost no air in it), which sir Boyle has never yet accomplished.]”

Huygens claimed that his pump was better than Boyle’s. That is, it had less leakage. And we have to say, reproducing his experiments four centuries later, that he must have been an excellent instrument-maker, as we were by no means able to seal our air-pump as tight as to keep it devoid of air for a whole night, not even if we cheated a bit by using 21th-century materials such as rubber and vacuum oil. As the descriptions of his experiments suggest that Huygens obtained certain experimental results with great ease, it is sometimes hard to believe he was telling the truth. It is easy to imagine that to his fellow experimentalists, to whom the facts established by the pump did not seem as evident as they seem today, this doubt was even more pressing. To believe or not to believe, that is the question. And one of the key elements to answer that question is the integrity of your experimental apparatus.

Given the difficulties of making an air-pump airtight, it is therefore not surprising that the question of leakage was always at stake. Philosophical theories were no longer to be sealed tight by the right definition, but through the refinement of the experimental apparatus. If the performance of a certain experiment did not give you the expected outcome, it was never clear whether this was due to a wrong hypothesis, or to a leaking pump. Despite the philosophical importance of the integrity of the apparatus, the mechanical work of optimizing it was often delegated to servants. (To this rule Huygens was an exception: although he, like many philosophers, came from a family of high standing, he constructed and operated his machine by himself).

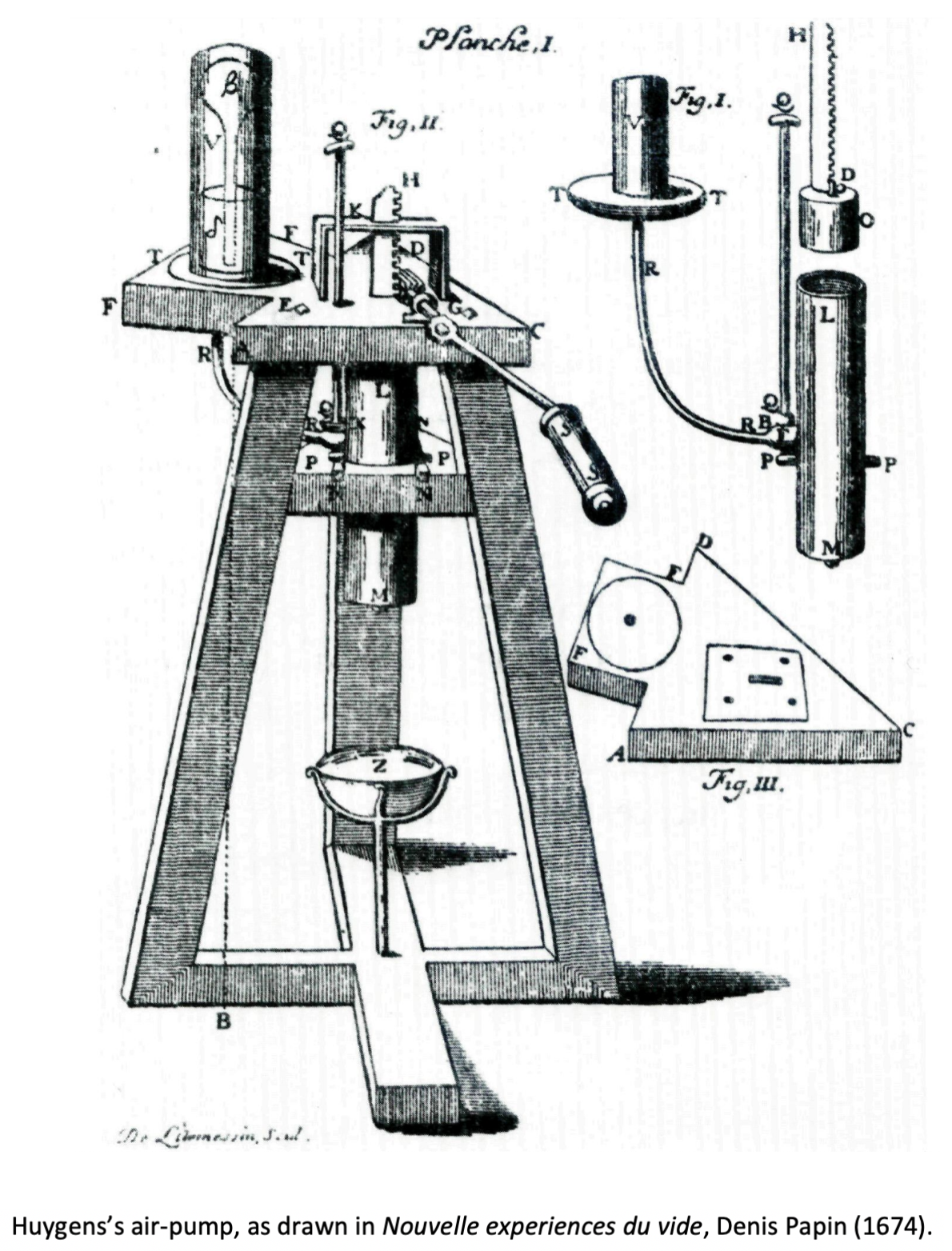

Huygens’s air-pump consists of a glass dome, a sucker in a cylinder, and a tap connecting the dome to the cylinder. Pumping air out of the dome goes as follows: first, the sucker is drawn up to the top of the cylinder, with the tap in closed position. Next, the tap is opened, letting a quantity of air from the dome into the cylinder. The tap is then closed again, and by pushing the sucker down, the air is pressed out of the cylinder through a valve at the bottom. Before every experiment, the area between the glass dome and the platform on which it rests needs to be sealed with what Huygens called ‘cement’, a mixture of beeswax and turpentine, to make it airtight.

A bladder or a piece of intestine was often used to test whether the pump worked or not. When the air around it is sucked out, the air in the bladder or intestine expands, making it grow. After a while, Huygens simply attached a piece of intestine to the side of his dome as a barometer.